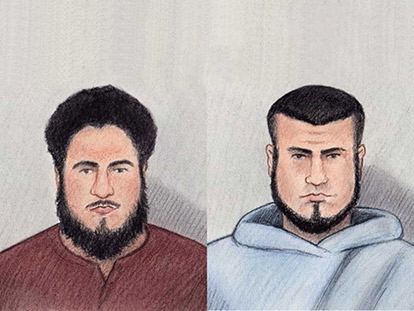

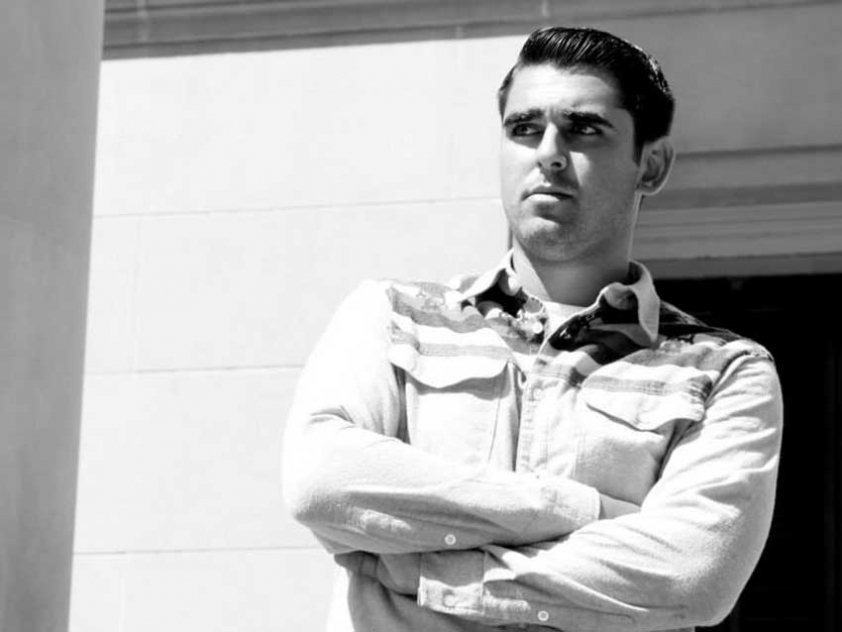

Shady Hafez, who is of Syrian Arab and Algonquin descent, reflects on what the closing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission means for him and his generation.

Courtesy of Shady Hafez

Shady Hafez, who is of Syrian Arab and Algonquin descent, reflects on what the closing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission means for him and his generation.

Courtesy of Shady Hafez

Jul

Truth and Reconciliation: A Young Indigenous Perspective

Written by Shady HafezShady Hafez, who is of Syrian Arab and Algonquin descent, reflects on what the closing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission means for him and his generation.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) held its closing ceremonies this past week. The TRC concluded by presenting an in depth report on the sad history and outcomes of the Residential School system. The TRC also prepared and presented a lengthy but comprehensive list of recommendations which it argues will help achieve reconciliation between Canada and the Indigenous inhabitants of this land. I agree fully with the TRC’s recommendations.

So what is this article about?

Well it’s about reconciliation, but more specifically this article is about a question I was asked regarding reconciliation.

That question was, “What does reconciliation mean to you?”

This question has really stumped me for some time. How could I possibly answer this question? I never experienced Residential Schools. I was never harmed or abused. Therefore, how could reconciliation mean anything to me? After some time spent pondering this question I was able to conclude that reconciliation does mean something to me. However, it may be different than what it means to many others.

I cannot speak on behalf of Residential School survivors nor can I ever say what they need or want to achieve reconciliation. I can only speak on behalf of my generation and myself, who have developed a different relationship with this State; built along the same foundations but expressed in a way quite different from how our parents and grandparents experienced colonization.

To start, while I have faith in the concept of reconciliation, I do not have faith in reconciliation happening between the Canadian State and us. For that reconciliation to happen Canada would have to abandon its archaic colonial practices and policies. As well, Canada would have to treat us in a way that would threaten its own “sovereignty” as a State. Now call me cynical but I don’t think that will ever happen. Therefore, I do not see us ever reconciling with the State of Canada. That does not mean we cannot reconcile with the church and with the Canadian populace. This reconciliation is very possible but it requires a major attitude shift. While that may be very possible with the various churches, I have a hard time seeing the Canadian populace suddenly having a major attitude shift within my lifetime. I mentioned that I am skeptical that we can ever reconcile with the Canadian State and now I am going to say something that some may disagree with entirely. As a young Indigenous person I don’t care much to reconcile my feelings of animosity towards this State. I am angry with Canada and I will most likely remain angry with Canada until I am grey and old. This State has shown time and time again that it does not want to achieve true reconciliation with us. Rather, it would prefer to have little shows of sympathy and apology to somehow wipe its own hands clean. That’s not how reconciliation works. As for the generations of Residential School survivors, reconciliation with the State may be fully necessary for their healing journey. It is not my place to comment on that.

That being said, can reconciliation happen between the Canadian State and Residential School survivors if it only happens through State-funded, mandated and controlled commissions?

There is no true answer to that question as forgiveness and reconciliation truly rests on the individual. However, how effective is any form of reconciliation when it happens according to the abuser's standard and comfort level?

I would argue not very effective.

Before I continue with my views on reconciliation I would like to add a few sentences on the lasting impression that the TRC closing ceremonies left with me. I honestly thought it was a shame that a time when Residential School survivors' stories should have been centre focus; they were instead overshadowed by speeches from the political elite of both the State and of Indigenous political establishments. The closing ceremonies should have been centered entirely on Residential School survivors. Their stories should have been broadcasted on live television, not the prewritten well-edited speeches of political leaders. Leaders Indigenous or not should have left the podium open for survivors to tell their stories to the cameras. Leaders like Thomas Mulcair and Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, Member of Parliament Bernard Valcourt, should have sat further behind, letting those survivors sitting in the back sit in the front. That is how support would have truly been shown. Valcourt should not have been given time on the microphone out of respect for how that may trigger the feelings of those survivors who may hold anger and rage towards that specific representative of the State.* Our leaders should have supported the woman who shouted in anger towards him; instead of awkwardly staring at her as if her anger was not justified. Overall, focus should have been given entirely to survivors and the closing ceremonies should not have turned into a showboating event for the political elite.

Now to return to my feelings on reconciliation; at this point it may seem as though I am completely bashing the State, which I may be on some level. However, what I would like to take out of this is that we as Indigenous people can still have a relationship with the State in terms of building a relationship where needs and wants are met. That relationship needs to be grounded in reality though. We must stop tricking ourselves into thinking reconciliation will happen on our terms with regards to mending the relationship between us and the State. We need to focus on nationhood and peoplehood. Look in, instead of out. Spend more time mending our own relationships before we mend whatever we think can be mended or salvaged between the State and us. Admit to ourselves that we will probably never have a healthy relationship between the State, a relationship built upon respect and reciprocity. The State will never allow the two-row** relationship to exist.

If we approach what we like to call the post-TRC relationship with this knowledge in mind, I think the relationship will be much more open and honest. Let’s stop smiling at each other for the sake of political ease and confront the actual feelings that linger in all of us. From there we may be able to build a genuine relationship built upon the understanding that we do not agree on whose land this is, what sovereignty means, who that sovereignty belongs to, and whether the State genuinely feels sorry for the atrocities committed. And would we not all rather they just say, “We don’t care get over it” instead of, “We are sorry”, followed by actions that portray that they are not sorry at all? At least then we could know what we are genuinely dealing with, opposed to thinking change will come, idly waiting for that day to come.

Now I did say earlier that I have faith in the reconciliation process. What I mean by that is that we, the Indigenous people of this land, need to reconcile with each other. Residential Schools have created a multitude of problems for Indigenous families here in Canada. Many of which have trickled down to my generation. Through intergenerational trauma and abuse, many Indigenous youth today are still dealing with the effects of Residential Schools. However, the difference between my generation and our parent’s or grandparent’s generation is that we are not facing this abuse from the government, school teachers, nuns or priests. Rather this abuse comes from mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, aunties and uncles. We all know this abuse happens and continues to happen in our communities. We all know families are broken. Many of our young parents do not know how to be parents. Many of our siblings do not know how to love each other. Knowing who is responsible for the original trauma does not change the fact that there is a new generation of abused children and broken families. I know many people would argue with me and say I am focusing on the negative; that so many young people are moving forward. We are. However, that does not change or negate that fact that many people are still dealing with the intergenerational aftermath of Residential Schools. Just because that fact happens to irk some of us or shame others does not mean it should not be discussed and addressed.

If we are ever going to rebuild our nations, then these relationships need to be reconciled. Money and time need to be invested in reconciling feelings between broken families, orphans, their parents, abusers and the abused. That’s where change is going to happen and that’s where change needs to happen. Hopefully the next step in our reconciliation process is what I just spoke about. We need to reconcile our feelings towards each other. That is what is going to help my generation and the generation of youth after me succeed and grow into healthy adults, parents, and eventually grandparents. A healthy nation is dependent upon healthy families. Reconciling the relationship between the Canadian State and us will not re-build broken families, nor will it provide the capacity for new families to grow in that manner. I will reiterate that we need to look in, re-build ourselves, and reconcile our own relationships amongst each other first.

This article is a republication of a blog post from Not Your Average Indian.

*MP Bernard Valcourt has upset some members of Canada's Aboriginal communities due to his comments in relation to Aboriginal youth suicide rates (See Vice News)

**"Two-Row" refers to the Two Row Wampum, one of the first treaties made between Haudenosaunee First Nation communities and European settlers. According to Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) historian Ray Fadden, the Haudenosaunee rejected this notion of a partriarchal between them and settlers and instead proposed: “We will not be like Father and Son, but like Brothers. [Our treaties] symbolize two paths or two vessels, travelling down the same river together. One, a birchbark canoe, will be for the Indian People, their laws, their customs, and their ways. The other, a ship, will be for the white people and their laws, their customs, and their ways. We shall each travel the river together, side by side, but in our own boat. Neither of us will make compulsory laws nor interfere in the internal affairs of the other. Neither of us will try to steer the other’s vessel.” Read this article in Briarpatch Magazine.

This article was produced exclusively for Muslim Link and should not be copied without prior permission from the site. For permission, please write to info@muslimlink.ca.